The United States Constitution does, of course, contain guidelines as to how a territory may enter the Union as a full-fledged state on an equal footing with all previously-existing states. The last time that any new states were added to the United States was in the year 1959 when Alaska became the nation’s 49th state and Hawaii became the country’s 50th state.

Specifically, the U.S. Constitution’s Article IV, Section 3, Clause 1 — which requires only a simple majority vote — reads:

“New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new States shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.”

There has been recent chatter about admitting Puerto Rico into the Union as the nation’s 51st state.

As the Constitution was not written until 1787 — and, once written, did not take effect until the following year — the procedure outlined within the still-in-force Articles of Confederation would have remained applicable to admission of news states up to the year 1788. The relevant provisions of the Articles of Confederation read:

“Article V. In determining questions in the United States in Congress assembled, each State shall have one vote.”

“Article XI. Canada acceding to this confederation, and adjoining in the measures of the United States, shall be admitted into, and entitled to all the advantages of this Union; but no other colony shall be admitted into the same, unless such admission be agreed to by nine [of the existing thirteen] States.”

In portions of present-day Tennessee (and in parts of what had once been North Carolina), there was an effort to create a “State of Franklin” (also referred to as the “State of Frankland” as well as the “Free Republic of Franklin”).

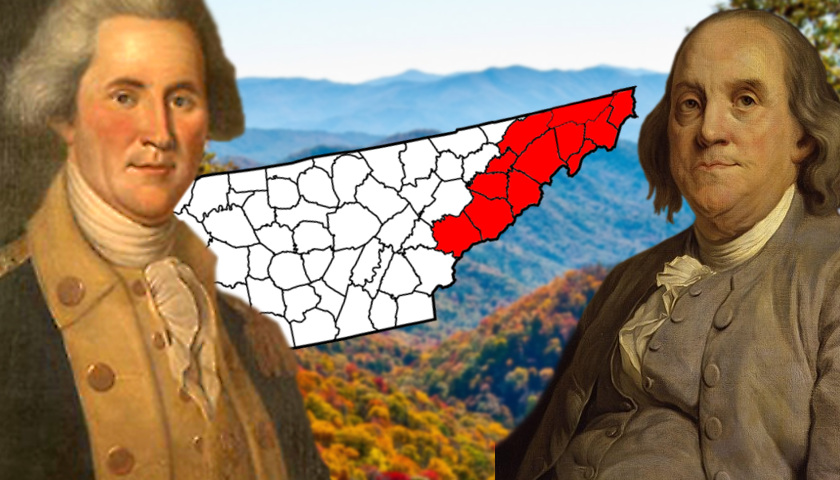

The territory which was sought to be the “State of Franklin,” for a brief quadrennium from 1784 to 1788, consisted of what is now extreme northeastern Tennessee (and no portion at all of present-day North Carolina): Blount County, Caswell County (modern-day Hamblen and Jefferson counties), Greene County (including modern-day Cocke County), Sevier County, Spencer County (modern-day Hawkins County), Sullivan County, Washington County (including modern-day Unicoi County) and Wayne County (modern-day Carter and Johnson counties). The alleged capital cities of the never-admitted “State of Franklin” were first Jonesborough (1784-1785) and then Greeneville (1785-1788).

On May 16, 1785, a delegation submitted a petition for statehood to the then-Continental Congress. Only seven states voted to admit the “State of Frankland” as the young nation’s 14th state — two votes shy of the necessary nine approvals as required by the above-quoted “Article XI.”

An effort was then made to secure the endorsement of Founding Father Benjamin Franklin in support of statehood by changing “State of Frankland” to “State of Franklin.” While flattered, Franklin wrote in a 1787 letter to future Tennessee Governor John Sevier (1803-1809) that “…being in Europe when your State was formed, I am too little acquainted with the circumstances to be able to offer you anything just now that may be of importance….”

Bitter factionalism was doubtless a contributing factor in denying those residing in this territory (at the time situated exclusively in North Carolina) any hope of actually convincing the Continental Congress to give the necessary two-thirds approval for this territory to officially be admitted into the Union as a state in its own right.

Another reason would be the fact that the entire controversy resulted from a cession (an offering from North Carolina to Congress) and a secession (when North Carolina’s offer to Congress was not acted upon and North Carolina then rescinded its offer).

North Carolina’s initial offer was spurred by the fact that the central government was heavily in debt at the close of the American Revolutionary War in 1783. To offset war debt, North Carolina generously wanted to give Congress 45,000 square miles lying in the region of Allegheny Mountains.

North Carolina’s gift contained a stipulation that the central government would have to accept responsibility for the area within two years which, for various reasons, Congress was reluctant to do. Later, a freshly-elected North Carolina General Assembly re-evaluated the situation. Realizing that the land could not, at that time, be used for its intended purpose of paying the war debts of the federal government — and weighing the perceived economic loss of potential real estate opportunities — North Carolina lawmakers rescinded the offer of cession and re-asserted North Carolina’s control over the region.

Not without a fight, however. North Carolina offered to waive all back taxes if “Franklin” would reunite with North Carolina’s state government. That offer was popularly rejected in 1787, and North Carolina moved in with troops to re-establish its own courts, jails, and government at Jonesborough.

When Tennessee, with boundaries known up to this day, was admitted into the Union in 1796, the disputed territory that was once informally the “State of Franklin” was assigned to Tennessee, and not to North Carolina.

– – –

With his decade of work (1982-1992) to gain the 27th Amendment’s incorporation into the U.S. Constitution, Gregory Watson of Texas is an internationally-recognized authority on the process by which the federal Constitution is amended.

Thank You. That is a meaningful contribution to ET history.